The Comic Pusher Presents The Run: Ex Machina Part One, The Pilot

In The Run

, I review long-form comic works across multiple parts. In Part One of my series on Ex Machina

by Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris, I introduce the series and look at the first issue, "The Pilot." Click here for my other reviews in the series.

Like so many

Brian K. Vaughan creations,

Ex Machina is a high-concept series with an easy-to-boil down premise - per Vaughan's own pitch,

The West Wing meets

Unbreakable - that stratospherically outperforms whatever reductive descriptions are applied to it. With the extraordinary efforts of illustrator and co-creator

Tony Harris,

Ex Machina is many things: it's an expansive science fiction epic grounded in the day-to-day grind of New York City politics, a parable about the corruptive effects of political power, the cost of the quest and exercise of powers (both political and supranatural), a portrait of a City and its People in the aftermath of its greatest tragedy, a ground-up reconstruction of the very concept of superpowered vigilantism, and above all else a profound tragedy.

Published between 2004 and 2010 by DC's moribund WildStorm imprint as one of its last marquis creator-owned works, the narrative largely focuses on the first term of political wunderkind Mitchell Hundred as Mayor of the City of New York between 2002 and 2005. The series chronicles New York's actual history of that time as well as the fictional history of Hundred's rise to power that begins as the world's only unlikely superhero. (Indeed, as the series was published, it overlapped with the actual history it chronicled.) As the series progressed over its 54 issues (or ten graphic novels encompassing the story's 21 chapters of varying lengths),

Ex Machina proactively touched upon the hot-button political issues of the day that frequently intersected with the New York City Mayor's office, examined the role of power and the price that quest has, told one of the few truly original modern superhero stories, and wove a unique and utterly absorbing mystery with mind-bending science fiction undertones that transformed the series' very identity and opens up even more layers of storytelling on the second readthrough.

The importance of

Ex Machina for both creators is pretty significant. Harris was already well-known for his

Starman comics with James Robinson, but

Ex Machina would prove to be his best, and longest cohesive work. Vaughan, by this point was well regarded for his work doing superhero comics with Marvel and DC.

Ex Machina, remarkably produced at the same time as

Y: The Last Man for Vertigo and

Runaways for Marvel showed Vaughan to be one of the brightest and most original new stars working in American comics. It is this trio of works that would make Brian K. Vaughan the writer that would co-create

Saga and

The Private Eye.

There are just a small handful long-form comic works from the previous decade that so fiercely capture the confusing and frightening sociopolitical aftermath of the September 11 attacks on the American identity, none as magnificently as

Ex Machina. With Garth Ennis's

Punisher Max, it is one of the two definitive works of the 2000's that question the role of power in our lives, a fiery masterpiece unequaled in its numerous literary achievements as a political drama and a piece of post-superhero science fiction commentary. As New York City approaches its municipal elections this November and its first new mayor since the aftermath of 9/11, I will be examining

Ex Machina, sequentially over several weeks followed by analysis of its many themes.

Ex Machina is a nuanced, complex and multilayered masterwork of contemporary American literature that merits close examination and multiple reads, and we begin with its extraordinary first chapter, "The Pilot."

--

Ex Machina's opening pages take place after the events of the series have concluded. On page one we see an image of a man in a sci-fi gee-wiz rocket-suit, and an airplane sharing the clear, blue sky with that man. We pull back to see that image on a wall in front of a man, scarred and alone, drinking in the dark. Talking directly to us, he references the image and the effects on history of what is depicted there. "This is the story of my four years in office, from the beginning of 2002 through godforsaken 2005. It may look like a comic, but it's really a tragedy."

The story begins to jump around in time. It's November, 1976, and the man, Mitchell Hundred, is a young boy reading superhero comics while his mom runs a polling station. Kremlin, a craggly Russian emigre who works out at Coney Island, shows up to take the kid off his mom's hands. Kremlin is a surrogate father to Mitchell, and one of the most important people in his life

... It's January, 2002, and Hundred is at a press conference, Mayor of New York, talking about small-town political minutiae that even the mayor of this massive, shining Metropolis must endure. A cry rings out, an irrational sounding accusation from a man with a gun. Hundred speaks, not the voice of a man but of something else, something very other: "JAM." And the gun jams, and the police take down the would-be assassin. Hundred's chief of security and his best friend, Rick Bradbury is angry at Hundred for using his powers - but even more furious when a reporter for

The Village Voice sneaks into the escaping motorcade

... It's October, 1999, and Hundred is a civil engineer, investigating a strange glow coming from the Brooklyn Bridge with NYPD marine patrol officer Bradbury. There is an explosion - half of Hundred's face is blown off. He screams at Bradbury, "Your radio is talking to me. The engine, your wristwatch, the entire City! Tell them to shut up!" In agony he screams, "SHUT UP!" and New York goes black

... It's February, 2000, and Hundred sits in a workshop with Kremlin, unemployed and making machines, the designs for which come to him in his dreams

... Months later, Hundred is flying around New York with a jet-pack as The Great Machine, plucking a skylark off off the 9 train, only succeeding at injuring the kid he meant to save and shutting down the subway system for hours

... It's June, 2001, and Hundred's a notorious if somewhat dubious superhero, revealing his identity in the offices of the City Councilman who would become his Deputy Mayor, the smart and skilled Dave Wylie. Wylie knows Hundred is more likely to simply end up in prison instead of Gracie Mansion, but is swayed by Hundred's seeming earnestness, independent streak and potential celebrity

...

Throughout these vignettes are effortlessly interlaced sequences taking place in the present day of January, 2002. Despite the assassination attempt, Hundred is more concerned with getting to the grind of running the City. There's controversy about a proposed smoking ban (Hundred is against it even though his staff is for it), he's just gotten a package from Kremlin (his old flight helmet), and someone from the Governor's office wants to meet him (with ulterior motives). The issue closes with Hundred meeting Kremlin in the shadow of Ground Zero, the wreckage of the World Trade Center still being cleaned up nearby. Hundred is returning the pieces of The Great Machine. He's left that part of his life behind, but Kremlin won't let it go. "I've done more in one hour at City Hall than The Great Machine did in a month." Kremlin objects, "How many more lives would have been lost if you had not put this on one last time?" Hundred, looking away, replies "No, I was a failure. If I were a real hero...

--

Everything that Vaughan and Harris will come to achieve in the years following the premier issue can be found reflected and brilliantly foreshadowed in that first issue. There is not a single action - not one panel of art or line of dialog - that is out of place or that won't have seismic consequences in the years and chapters to come. Evident are all the elements that would come to define the series: Hundred's independent political voice and his upbringing marked by political activism and superhero comics, the minor and major crises that arise daily in the Mayor's office, his role as a superhero of dubious stature, the relationships and traits of the main cast of characters, the overarching mystery of the source of Hundred's powers, the setting and history of post-9/11 New York City and Hundred's profound impact on that history, and even the series' frequent use of misdirection and wordplay. In a modern tradition of long-form (fifty or sixty issue) stories, in

Ex Machina Vaughan reveals himself to be a storyteller of uncommon vision and skill.

|

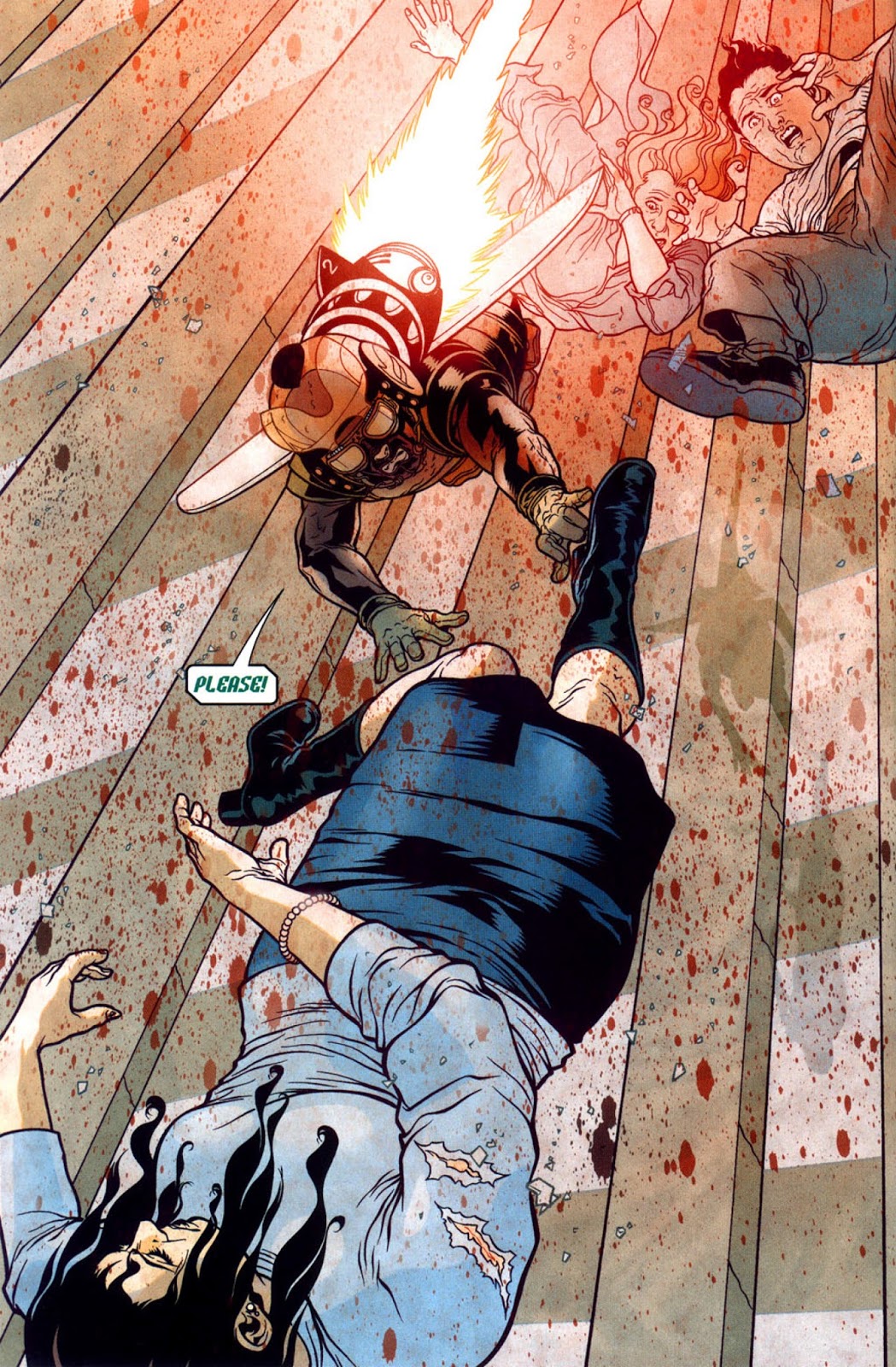

| Examples of Vaughan and Harris's intricate storytelling. |

Ex Machina has two notable storytelling trademarks immediately evident from its first chapter: Vaughan's complex nonlinear narrative, and Harris's vivid photo-referenced art. The issue opens after the conclusion of the series' narrative, and jumps around in time between the present of Hundred's mayoralty beginning in 2002, multiple looks at his career as an erstwhile superhero from 2000-2001, his origin in 1999, and his childhood in the 1970s. Vaughan effortlessly weaves in and out of these seemingly disparate narratives and connects them into a brilliant and subtle superstructure.

Harris's art is vivid and expressive. Using extensive casting and photographic referencing, Harris produces dynamic set-pieces without ever falling into the traps of formal stiffness that so many photoref'ed artists fall to. Aided by the bold lines of inker Tom Feister and the masterful coloring of JD Mettler, Harris skillfully bounces between long stretches of character dialog and short bursts of explosive action.

In the past I have often described

Ex Machina as "incidentally a superhero comic." Ultimately,

Ex Machina, despite its high concept, is not a book that is inclusive or exclusive of the many genres it comfortably flirts with. It's nature as a superhero work is vital to the book's identity - Mitchell Hundred is superpowered, with the ability to communicate with electronics and even simple machines. But the way the series approaches the idea of superheroism is unique. By anchoring the events of the comic in the real world, or as close a facsimile as this reasonably can be called, the approach to vigilante justice done with an eye to the logical implications of such a being interacting in the world. It is immediately evident that Hundred is well-meaning but more often than not is a bumbling fool who occasionally just gets in the way rather than being the hero of his superhero comic reading youth. The shocking twist that he stopped the second plane on September 11 and parlayed that genuine heroic effort into political gain is something that will be touched upon at greater length as the series moves forward to its brilliantly foreshadowed tragic conclusion.

It is the tragedy Hundred straight-out tells us about on page two that is almost never referenced, which is part of the series' genius misdirection. It isn't forgotten about, the business of running the City just takes center stage. But after the series concludes, the shockingly subtle foreshadowing at work in this issue and throughout the entire series adds layers to the storytelling that cannot be guessed looking at these thirty pages. As a stand-alone work,

Ex Machina #1, "The Pilot" - a triple meaning referring to Mitchell Hundred the character, self-referentially to the first episode of a series, and to something else yet to be revealed - is a nearly perfect comic that adeptly introduces the cast, the past, and the conflict going forward. But within the context of what will ultimately follow, "The Pilot" is a breathtaking, flawless, visionary comic, a stunning masterpiece and an auspicious beginning to one of the finest long-form comic stories ever told.

--

Ex Machina #1, "The Pilot" (DC/WildStorm, June 2004) is collected in

Ex Machina Volume 1: The First Hundred Days (February 2005) and in

Ex Machina: Book One (Hardcover, June 2008; in softcover January 2014 from Vertigo)

-17.jpg)